Back Page: Risk Assessment

Pharmaceutical Executive

Genomic researchers are developing tools to determine whether the right patients are taking statins.

Evidence that inflammation—not just blocked arteries—may be a leading cause of heart attack and stroke has triggered a race among genomic researchers to develop sophisticated new screening tools. It also could mean big changes in how risk is assessed.

Sunshine K. Mugrabi

For years, physicians have identified candidates for statin therapy primarily by a measure known as the Framingham risk score, which is based on a number of factors for both men and women: age, total cholesterol, LDL-and/or HDL-cholesterol levels, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking. It doesn't take into account genetics or family history.

The problem, says Paul Ridker, MD, a physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, is that "half of all heart attacks and half of all strokes occur in people with normal cholesterol."

In 1997, Ridker and his colleagues found that high levels of an inflammatory marker known as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) conferred a threefold risk of heart attack, compared with the 1.6-fold risk associated with elevated LDL-cholesterol. The conclusions were based on analysis of blood samples from 543 subjects in a large-scale, 13-year-long study.

The theory behind this: inflammatory proteins contribute to the development and eventual rupture of atherosclerotic plaques. In other words, they are markers for and contributors to heart disease.

Statins, in addition to acting on LDL-cholesterol, also reduce such inflammatory proteins by up to 30 percent. To test whether this aids in statins' effectiveness, Ridker is leading a 15,000-patient trial of Crestor using subjects with low cholesterol and high hsCRPs. The results, expected within three years, could cause a sea change in the way risk is assessed.

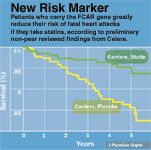

New Risk Marker

In light of such research, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute released recommendations in December 2005 that the Framingham score be modified to include hsCRPs, along with novel biomarkers found through genomics, proteomics, and other cutting-edge methods.

Meanwhile, genomics firms worldwide are developing diagnostic tests and even drugs that build on this model of heart disease. In the coming months, Celera Diagnostics expects to roll out two genetic screening tests that its president, Kathy Ordoñez says will detect heart attack and stroke risk, and reveal which patients are most likely to benefit from statins.

Celera's first diagnostic tool, which Ordoñez says will likely be on the market within the next several months, offers a genetic risk assessment based on a small set of genes that are strongly associated with either increased risk of heart disease or protection against it. The cost to patients will be in the "hundreds of dollars per test," says a Celera spokesman, far cheaper than most genetic tests, but significantly more expensive than testing for LDL-cholesterol or hsCRPs.

Celera also is developing a test to determine whether a person responds well to statins. The new test also will debut within "months, not years," says Ordoñez The test focuses on several genetic markers. One, FCAR, was found to virtually eliminate a carrier's risk of a fatal heart attack when taking statins. The results also seem to show that FCAR carriers who do not take statins are in significantly more danger of fatal myocardial infarction than non-carriers.

Celera hardly has the field to itself, as many other genomics outfits—all of which have access to gene-sequencing tools and publicly available genetic data—are working on similar tests.

There also are some doubters, including Ridker, who says he doesn't believe that currently "there are any genetic risk factors worth measuring ... that will help predict the risk of heart attack or stroke and that would change a physician's practice."

In spite of this, genomic research of the link between heart disease and inflammation continues apace, and if successful, could shift the paradigm of detection and treatment of the Western world's number-one killer.

Sunshine K. Mugrabi is a freelance business and science writer. She can be reached at skd2111@columbia.edu

Key Findings of the NIAGARA and HIMALAYA Trials

November 8th 2024In this episode of the Pharmaceutical Executive podcast, Shubh Goel, head of immuno-oncology, gastrointestinal tumors, US oncology business unit, AstraZeneca, discusses the findings of the NIAGARA trial in bladder cancer and the significance of the five-year overall survival data from the HIMALAYA trial, particularly the long-term efficacy of the STRIDE regimen for unresectable liver cancer.

Cell and Gene Therapy Check-in 2024

January 18th 2024Fran Gregory, VP of Emerging Therapies, Cardinal Health discusses her career, how both CAR-T therapies and personalization have been gaining momentum and what kind of progress we expect to see from them, some of the biggest hurdles facing their section of the industry, the importance of patient advocacy and so much more.

Talphera Cuts NEPHRO CRRT Study Size, Secures $14.8 Million Private Placement

April 1st 2025The trial size adjustment, along with protocol modifications and the addition of higher-enrollment sites, is expected to facilitate completion of the NEPHRO CRRT study of Niyad in patients undergoing renal replacement therapy by the end of 2025.