Regulatory action makes Rybrevant plus chemotherapy the first FDA-approved therapy for the first-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations.

Regulatory action makes Rybrevant plus chemotherapy the first FDA-approved therapy for the first-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations.

The latest news for pharma industry insiders.

JAMA commentary suggests that issues such as high costs, access, and equity will stop patients from obtaining GLP-1 agonists to treat obesity.

New guidance suggests that CMS may be ramping up Sunshine Act auditing activities, potentially resulting in monetary liability for noncompliant reporting entities.

Phase III DAYBREAK study found consistent safety with Zeposia in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis.

Cardinal Health report highlights new biosimilar treatments, legislative developments, and multiple industry perspectives.

IDP-023 is a highly potent natural killer cell platform under evaluation for patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Commentary cites lower control over health plan costs and the potential bias for prescribing drugs through influence from drug manufacturers.

Abrysvo was found to produce durable efficacy against respiratory syncytial virus across two seasons in adults 60 years of age and older.

OSE-230 was developed to activate a unique mechanism for resolving chronic inflammation, focusing on modulation of macrophages and neutrophils.

The trial reportedly showcased significant weight reduction in those treated with VK2735, a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist.

Trogarzo (ibalizumab-uiyk) is currently approved in combination with other antiretroviral therapy for heavily treatment-experienced adults with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection who are failing their current antiretroviral regimen.

NVL-520 is a novel, brain-penetrant, ROS1-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor under evaluation for patients with metastatic ROS1-positive non–small cell lung cancer.

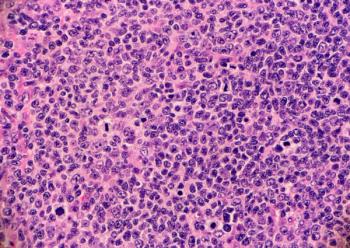

Agency identified several clinical deficiencies in the study, including insufficient evidence for roluperidone in the treatment of the negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

The device can detect potential warning signs of serious conditions.

The FDA granted Allecra with a five-year marketing exclusivity extension for Exblifep (cefepime/enmetazobactam) through the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now Act.

New label marks the first Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor to be approved with an oral suspension formulation.

Results of the study determined that adult flu vaccination rates among Medicaid populations were significantly low, highlighting other health inequities.

Trial data support Tevimbra combined with chemotherapy as a potential first-line treatment option for patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer.

Epkinly (epcoritamab-bysp) is a subcutaneously administered, T-cell engaging, immunoglobulin G1-bispecific antibody under evaluation for aggressive B-cell lymphomas.

Biktarvy approved for expanded indication to include patients with HIV who have suppressed viral loads with known or suspected M184V/I resistance.

In an interview with Pharm Exec Associate Editor Don Tracy, Arun Krishna, VP, Head of US Lung Cancer Franchise, AstraZeneca, talks about the FDA's approval of TAGRISSO with the addition of chemotherapy in adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated non-small cell lung cancer.

A Harvard Business School Healthcare Alumni Association (HBSHAA) Q&A with Professor Deborah Ancona, founder of the MIT Leadership Center.

Murray Aitken, Executive Director of the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, discusses how climate events and COVID-19 have impacted medicine use and spending.

In the EAGLE-1 Phase III trial, gepotidacin met the primary efficacy endpoint of non-inferiorty to the current leading treatment for uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea.

BAY 2927088 is an oral, reversible small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor being analyzed for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with tumors that have activating HER2 mutations.

The site will have a staff of 400 employees.

Collaboration aims to leverage Nhwa’s expertise in the country’s neuro-psychiatric health sector.

Survodutide, a GLP-1 receptor dual agonist with a novel mechanism of action, was the first treatment to produce findings this significant in a Phase II trial of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

Results of a study conducted by the National Institutes of Health indicate that the Paxlovid prevented a substantial number of hospitalizations associated with COVID-19.