The Big Squeeze

Pharmaceutical Executive

Between now and 2008, $40 billion worth of pharmaceutical industry revenues are at risk through patent expiration on just 19 products in the United States alone. Worldwide, a much more dramatic $72 billion stands to be lost.

Between now and 2008, $40 billion worth of pharmaceutical industry revenues are at risk through patent expiration on just 19 products in the United States alone. Worldwide, a much more dramatic $72 billion stands to be lost.

Leading Practices in Lifecycle Management The promise of lifecycle management is that modest improvements will work together to create large results. This chart estimates realistic, achievable results in some key areas.

Those revenues will not be replaced primarily by new blockbusters; more likely, in the near future, pharma will be looking at products in the $500 million to $600 million range. If so, pharma will need 80 new molecular entities (NMEs) in the next four years to replace lost US revenue—and 144 to make up for lost revenue worldwide.

One needn't be a pessimist to conclude that this isn't going to happen. The current drought in new products is unlikely to be resolved in the short term, and many industry observers believe the only way pharmaceutical companies will survive and prosper will be through more sophisticated lifecycle management. "We're going to be more dependent on existing product pipelines," said Chris Towler, former director of global regulatory policy at Glaxo Wellcome. "Smart companies will look to wring everything they can out of their existing products."

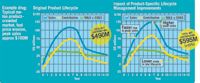

Lifecycle Managements Impact at the Product Level These graphs show what happens when several dimensions of a product are managed simultaneously. With quicker time to peak sales and effective late-stage cost controls, a 13 percent increase in sales translates to a 22 percent increase in profit contribution.

In a survey of pharmaceutical executives conducted by Capgemini, only about one-third rated product life cycle management as either a number-one or number-two priority in recent years. Ninety percent believe its importance will increase in the next five years, with 60 percent saying it would increase significantly from its importance today to be the top or second priority for drug companies. Apart from the need to develop innovative new drugs, no other business issue preoccupies senior pharmaceutical executives as much. As one put it, "If innovation is the number-one priority, product lifecycle management is number two."

Focus on Contribution

The main reason for product life cycle management's rising importance is simple, according to executives in the survey. With fewer truly innovative drugs in the pipeline and with the cost of bringing new drugs to market rising dramatically, companies need to maximize the value of existing products. "We have used product lifecycle management in the past as though it wasn't really very important—but the blockbusters are not around the corner anymore," explained one respondent.

Driving Change at the Portfolio Level Many companies face declining revenues because of patent expiries and price pressures. Lifecycle management can potentially preserve profits in a difficult business environment.

Nonetheless, fewer than 20 percent of executives rate their companies' current execution as excellent and 30 percent as good. Thirty-five percent say their companies are average, while more than 15 percent believe they do a poor or very poor job of managing product life cycle.

There are several reasons why companies might be falling short of their expectations in lifecycle management. Life cycle strategies are not adopted early enough, and confused governance undermines their effectiveness. Strategies are often developed from functional perspectives, rather than an overall business perspective. Organizational boundaries—between business functions such as R&D, marketing and sales and manufacturing, as well as between global product teams and the subsidiaries—make it difficult to adopt a cradle-to-grave approach. "Responsibility shifts from function to function through the lifecycle of the product," stated one European executive.

What is more, the focus is often on the wrong goal. In many companies, life cycle strategies are evaluated primarily in terms of top-line growth. That may have been adequate when pipelines were full. But what is needed today is an integrated, holistic approach that aims to maximize not the lifetime revenue of the individual product, but the lifetime profit contribution of the whole portfolio.

Modeling Impact

To achieve this goal, companies must build new competencies. Financial management and insights will have to improve, so companies have a clear picture of what it costs to bring each product to market. Simply dealing in average numbers won't be acceptable. This new understanding of costs will feed decision making about the portfolio.

The promise of lifecycle management is that modest, achievable improvements in multiple dimensions will lead to large effects on profitability. That makes intuitive sense, but it isn't necessarily easy to demonstrate. Over the past few years, Capgemini has been working on modeling the financial impact of life-cycle management. The charts accompanying this article summarize some of that research.

The chart on page 88 lists principal elements of an integrated life cycle management program and estimates the scale of improvements that seem achievable. We estimate, for instance, that clinical trials can be accelerated by three to nine months through more efficient patient enrollment, predictive modeling, and the like; that the use of inexpensive sales channels can reduce costs by 50 percent in the late phases of the lifecycle; and peak sales can be reached three to nine months earlier.

Different companies, of course, will have different results. The point is the impact when these improvements are applied simultaneously. The two graphs on page 90 look at a single product—a me-too drug in a crowded marketplace. The two graphs may not look terribly different—the sales line rises to peak a little more quickly, the peak is about 13 percent higher, and costs are lower during the fall-off of sales. But the impact on profitability is substantial. The modest changes to cost and sales increase the product's contribution by more than 20 percent.

The third chart takes the same sort of analysis to the level of the whole company. Here, we model the performance of a large pharma company over five years of patent expirations and price pressures. If the company performs at its current standard, profits rapidly erode—something that will be happening over the next few years to companies that don't rise to the challenge of today's marketplace. With lifecycle management—even if we assume that only part of the benefits can be realized in the five-year time frame—the picture is quite different. Sales rise by $500 million, and the whole increase appears in the form of operating profit.

The Elements of Success

What are the ingredients of successful product lifecycle management? One of the difficulties in defining best practices is the relative immaturity of lifecycle strategies in the pharmaceutical sector. For a variety of reasons, product lifecycle management is more entrenched and sophisticated in the more consumer-oriented industries. Even so, there are plenty of examples of good practice and innovative product management in the pharmaceutical industry to draw on.

Sustain value through proactive planning. Whether through identifying follow-up indications, planning new formulations, or creating a consumer brand in readiness for an OTC switch, success depends on early planning. "Ten years ago lifecycle management was about what to do once the product was on the market. Now, even at the stage of preclinical development, we need to know what indications we're going for and what dosage forms we will need," explains a vice-president of global business development and licensing at a large pharmaceutical company.

Consider Bayer's success in evolving Adalat (nifedipine) to address new markets. The product was launched in the mid-1970s as an anti-anginal therapy, taken three times a day. Bayer expanded Adalat's label to include hypertension, introducing a long-acting form to address this lucrative market in 1985. As a result, Adalat sales continued to grow until they exceeded $800 million a year by the early 1990s. By 1991, Bayer had again laid the groundwork for a new form of Adalat, this time releasing a once-daily dosage form to match the emergence of competitive products with a similar duration of action. As a result of Bayer's success in identifying new indications and dosage forms early in Adalat's lifecycle, its sales continued to climb to $1.17 billion by 2000—a quarter-century after the drug was first commercialized.

Speed the product on its way. The cost of bringing a major pharmaceutical product to market is estimated to more than $879 million. Of the R&D costs (about 70 percent of the total), the later stages are by far the most expensive; phase I, II and III clinical trials represent 35 percent of all R&D outlays. Although the focus of attention at this stage is naturally on getting the product approved by regulatory authorities, it is important in the total context of product lifecycle management that vigorous prelaunch activities are under way to create heightened awareness of the forthcoming product.

Launch acceleration is now a vital ingredient in product lifecycle management, because every month shaved off the time to market can be measured in additional sales. PPD, a provider of services to assist drug discovery and development, illustrates this using the example of a fictitious product having annual revenues of $11 billion, gross profit of $8.8 billion, operating income of $3.3 billion, and operating income/share of $1.12 billion. According to PPD, if this company could bring a $2 billion blockbuster product to market three months earlier, it would increase its operating income by 14 cents per share. If the product could be brought to market six months faster, operating income/share would rise by 27 cents.

Comarketing can be a potent means of ensuring that a product reaches peak sales quickly after launch. Crucial to GlaxoSmithKline's marketing of Zantac (ranitidine) was a policy of selecting comarketing partners, such as Menarini in Italy, the country where Zantac was launched. This was especially valuable in countries such as Italy, Germany, and Japan, where GlaxoSmithKline did not, at the time, have a high profile among physicians; its marketing partners were chosen as native companies with a good but not overwhelming presence. Having two sales forces ready to promote their brands of ranitidine meant that early product growth exceeded all expectations. It was also an excellent boost to company morale in other countries.

Create a franchise. A therapy franchise is more than the sum of its parts. It is about dominating a particular therapeutic area through the creation of a complementary range of products. The range may be as few as two; in the hypertension field, AstraZeneca has the angiotensin II antagonist Atacand (candestartan cilexetil), which had an 8.7 percent share of the market (but 65 percent growth rate) in 2000. But AstraZeneca also has another antihypertensive, its ACE inhibitor Zestril (lisinopril). Zestril forms part of the same therapy franchise with Atacand, which is recommended in the treatment of mild-to-moderate hypertension, while Zestril is used in more severe cases. By treating the two as complementary products, AstraZeneca has been able to sustain Zestril's growth while launching and growing Atacand. This flies against the predictions of many analysts, but the facts are there: Atacand is challenging the market leader Cozaar (losartan), which is produced by Merck.

Not every company is fortunate enough to have two successful products in the same therapeutic area. Our survey reveals that in-licensing is emerging as a favored means of developing a franchise, by adding products that complement the uses of an existing successful brand.

Enlarge the playing field. One of the most familiar, and favored, tactics in product lifecycle management is expanding the uses of the product. Bayer's Adalat is just one example of a group of drugs that were introduced as treatments for angina and went on to achieve greater commercial success as antihypertensives. Indication expansion is also tried and tested in the psychotropic field, where diagnostic distinctions can be blurred and a drug initially promoted as an antidepressant may later find a niche in, for example, bipolar disorders. In gastrointestinal disease, it is now commonplace for drugs such as proton pump inhibitors to have a wide range of licensed indications, from full-blown peptic ulcer to dyspepsia.

Prolong the effect. Some drugs taken orally are absorbed from the stomach, but most reach the bloodstream from the small intestine. Thereafter, unless they have inherently long half-lives, their useful life in the bloodstream is around four hours. The inconvenience of having to take tablets so frequently was the spur for the growth of the industry's drug-delivery sector. Special drug-delivery formulations were mainly intended, at first, to achieve 12-hourly or even once-daily dosing.

The best-known example of an early sustained-release formulation is Voltaren Retard (diclofenac) from Ciba (now Novartis). The original Voltaren was a first-generation nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Introduced from the early 1970s onward, NSAIDs revolutionized the management of arthritis and rheumatism. But the first-generation drugs were all short-acting and had to be taken three times a day. Already, second-generation candidates with inherently longer action were in the pipeline. But Ciba beat them to the market by launching a sustained-release form of its already highly successful Voltaren. The result was that Voltaren became, and remained, the most successful NSAID of them all.

The technology that is available to drug-delivery formulation scientists is far more advanced than simply making long-acting oral dosage forms. Transdermal patches and various inhalers have been familiar for many years, and there is ongoing research into newer, patient-friendly methods of administration, such as an inhalation form of insulin. Dosage-form innovation continues to be an important means of refreshing an established product and perhaps of expanding its usefulness.

Protect innovation. The importance of protecting pharmaceutical intellectual property is well recognized. Like other aspects of product lifecycle management, this should be considered at an early stage in a product's development. The increase in regulatory stringency in the 1970s and 1980s eroded the period of patent cover left to a product by the time it obtained marketing approval, but the Hatch-Waxman Act in the United States and the Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPC) measures in the EU meant that companies could effectively recoup the time a product lost due to regulatory delays. This greatly reduces the risk of losing exclusivity by filing early. However, there have been developments affecting the later stage of patent cover, and companies should be aware of them when contemplating the defense of a product against impending generic competition.

Go public. Branding is of far greater importance for OTC products than it is in the prescription marketplace, and failure to recognize this is probably a major reason why Rx-to-OTC switches have so often failed. A switch must be planned, according to some authorities, while the product is still in pre-licensing clinical trials, and certainly at least seven or eight years before the switch is made. This time is necessary to lay the groundwork for introducing the product as a consumer brand.

GSK's success in switching Zovirax (aciclovir) from prescription to OTC in the UK is a good example of the value of early planning. It was launched as self-medication for the treatment of cold sores in 1993, three years before patent expiry. Sales switched from the prescription product to the OTC version, which continued to maintain sales and to retain an OTC market share of more than 90 percent in subsequent years. Zovirax still sells at around $15 million per year at retail prices.

Prilosec and its evolution into Nexium provides an interesting case of an OTC switch that was managed in parallel with the launch of a successor to the original prescription brand. Prilosec was AstraZeneca's proton pump inhibitor with the generic name omeprazole; it was approved by the FDA in 1989. The company developed a derivative, esomeprazole (the s-isomer of racemic omeprazole), which was approved by the FDA in 2001. Nexium was launched in 38 markets in 2001, and in 2003 it was the fastest-growing product in its class, with sales up 62 percent year-on-year to $38 billion. Meanwhile, the patent on Prilosec had expired in October 2001, and the company obtained FDA approval for an OTC version, which was launched under the Prilosec name in December 2002. This complementary strategy enabled AstraZeneca to sell the established brand of Prilosec over the counter, while also marketing a follow-on prescription product under the Nexium brand.

Know when to leave the field. Product lifecycle management is about profitability, and the process must include a means of holding a yardstick to the financial contribution of every product so that those that no longer deserve a place in the portfolio can be discontinued or sold. Obvious as this seems, some companies continue supporting products that have long ceased to be profitable.

One of Capgemini's clients in the pharmaceutical industry recently undertook a wide-ranging review of the profitability of each of its products, and uncovered some surprising facts in the process. Thirty-six percent of the company's product lines proved to be unprofitable, of which more than 95 percent were out of patent protection.

It also transpired that more than half the company's subsidiaries had five or more unprofitable products, and only one out of the company's 16 product families was supported by a product lifecycle strategy. As a result of this exercise, the company found that savings of 15 percent of the cost of supply operations could be achieved by dropping unprofitable product lines.

There is an understandable reluctance to slim down product lines in these days of pipeline drought, but the years ahead will not be kind to companies that persist in carrying dead weight. More robust metrics for understanding the real contribution of each product to the business will be essential if companies are to identify and properly support the top-performing products of the future.

A New Capability

Lifecycle management will be the most important capability for pharmaceutical companies to develop. This will affect all their efforts across the value chain and will require not just an activity approach but one that builds an organizational capability in individuals, one that influences thinking, behaviors, governance, and performance metrics. This capability needs to be applied to the keys to success, which we prescribe to be:

- Start early and plan ahead

- Collaborate across all business functions

- Introduce a broader business perspective

- Focus on profitability throughout the lifecycle

- Establish clear leadership.

This integrated, holistic approach will ensure that firms that embrace these ideas will maximize the economic impact of their product potential.

Addressing Disparities in Psoriasis Trials: Takeda's Strategies for Inclusivity in Clinical Research

April 14th 2025LaShell Robinson, Head of Global Feasibility and Trial Equity at Takeda, speaks about the company's strategies to engage patients in underrepresented populations in its phase III psoriasis trials.

Beyond the Prescription: Pharma's Role in Digital Health Conversations

April 1st 2025Join us for an insightful conversation with Jennifer Harakal, Head of Regulatory Affairs at Canopy Life Sciences, as we unpack the evolving intersection of social media and healthcare decisions. Discover how pharmaceutical companies can navigate regulatory challenges while meaningfully engaging with consumers in digital spaces. Jennifer shares expert strategies for responsible marketing, working with influencers, and creating educational content that bridges the gap between patients and healthcare providers. A must-listen for pharma marketers looking to build trust and compliance in today's social media landscape.